Mound Deposits and Reefs

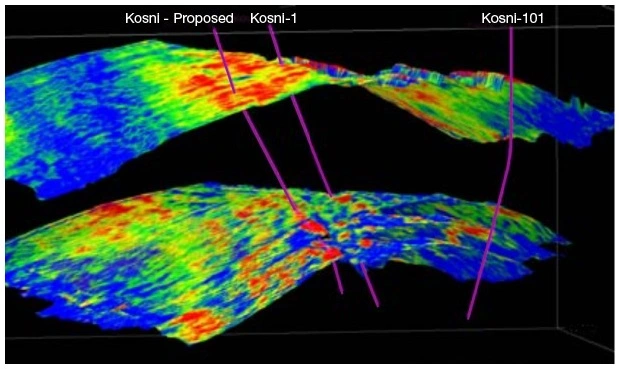

Seismic detection of reefs is important in oil and gas exploration. This is because of the usually high volumes of producing hydrocarbons found in localized instances, requiring relatively smaller production effort as opposed to larger or more complex geologic targets.

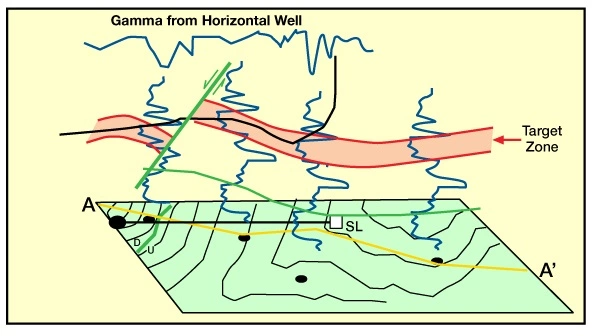

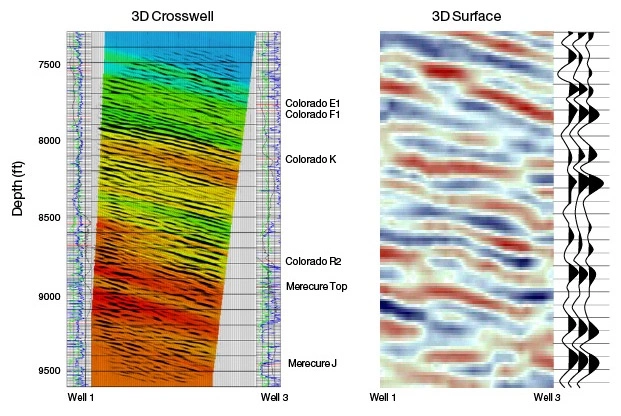

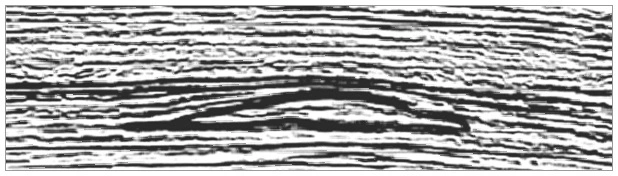

In Figure 1, a mound of some sort has formed on the ancient sea floor. Sediment, moving to its final depositional site by the usual mechanism of bottom transport, onlapped the mound until it was covered and the mound disappeared beneath an even and horizontal sheet, now represented by the strong reflection. Sedimentation continued for a period now equivalent to 50-100 ms of reflection time, but during this period the compaction of the onlapping sediments on each side of the mound caused the strong reflection to drape over the mound. Then the compaction stabilized, and a considerable thickness of sediments was deposited, on a nearly horizontal surface of deposition over the whole section. Finally, the weight of these later sediments renewed the process of compaction. The later compaction, like the first, was greater in the off-mound sediments than in the mound itself, and so the whole section above the mound now shows conformable drape over it. The conclusion from this example is that the sediments off the flanks of the mound are rich in shales, while the mound is rich in either carbonates or sands.

Important examples of such mounds, in a reservoir sense, are sand-rich submarine fans and carbonate build-ups of biothermal or biostromal origin (a bedded sedimentary deposit of organic origin built by marine organisms, which includes shell beds, flat reefs, and corals).

In the latter context, a particularly important target is the reef. Reefs have a natural habitat and grow systematically at a hinge-line or edge of the shelf (shelf-edge or barrier reefs), or in isolated fashion from a carbonate platform on the shelf (patch reefs). Some reefs have a characteristic form, representing the style of growth, the effect of wave action, and the types of sediment deposited around and over them. Sometimes, therefore, reefs may be identified directly on the seismic section by first looking for a shelf or shelf-edge environment, and then looking for the characteristic form.

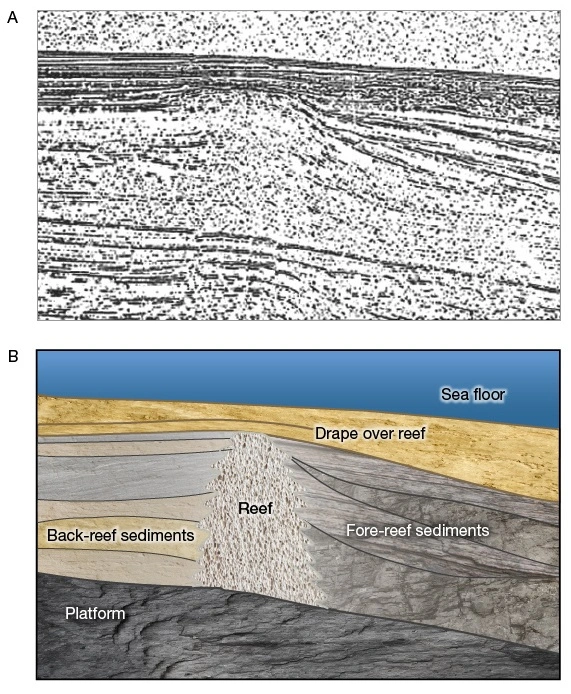

Figure 2 shows what we might hope to see on a line perpendicular to the shelf edge; image A is the section, and image B is an interpretation showing the important features. We notice in particular the reef itself (characterized by few or no internal reflections), the difference of appearance between the back-reef and fore-reef reflections, and the draping of later sediments over the reef.

When the reef characteristics are as evident as the above example, the search for reefs is simple and direct, particularly for patch reefs. However, the identification of reefs is not always easy. Often drape is our sole indication of reefs, and this occurs only when the flanking sediments are more compactible than the reef.

Petro Shine The Place for Oil and Gas Professionals.

Petro Shine The Place for Oil and Gas Professionals.