Directional drilling or slant drilling is the practice of drilling non-vertical bores and accessing an underground oil or gas reserve, directional drilling is also called directional boring It can be broken down into four main groups: oilfield directional drilling, utility installation directional drilling (horizontal directional drilling), directional boring, and surface in seam (SIS), which horizontally intersects a vertical bore target.

History Directional Drilling

“There’s no such thing as a straight hole.”

Anonymous

All wells, whether by accident or by design, exhibit changes in hole angle and direction. Although borehole deviation has likely been a reality since the heyday of cable-tool rigs, it was the advent of rotary drilling that made the phenomenon painfully evident. For example:

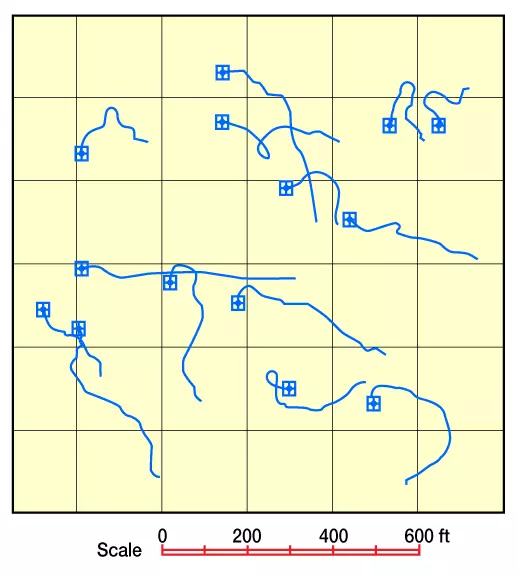

- Operators found that supposedly vertical wells exhibited large horizontal departures (Figure 1, Plan view of 14 “vertical” wells drilled to 6000 ft). Suman (1940) describes two California wells whose surface locations were 2000 ft [610 m] apart, but that ran together at a measured depth of 6115 ft [1864 m].

- Wells frequently drifted across lease boundaries, causing no end of legal problems.

- Abrupt hole angle changes known as doglegs led to drill string fatigue failures because of the increased stress they placed on tubulars. They also caused the pipe to work itself into the borehole wall, forming key seats that often resulted in stuck pipe.

Crooked hole tendencies were considered early on as a serious drawback to the widespread use of rotary rigs. But the benefits of rotary drilling more outweighed this perceived limitation, and so the industry began developing ways to keep wells on course. Thus was born the science, or perhaps more accurately, the art of deviation control.

Once the industry began devoting serious effort to limiting wellbore deviation, it was natural to start working toward the next step of actually guiding the drill bit to a specific downhole target: a practice known as controlled directional drilling.

Petro Shine The Place for Oil and Gas Professionals.

Petro Shine The Place for Oil and Gas Professionals.