Lithology, Rock Type, Color and Thickness of Units

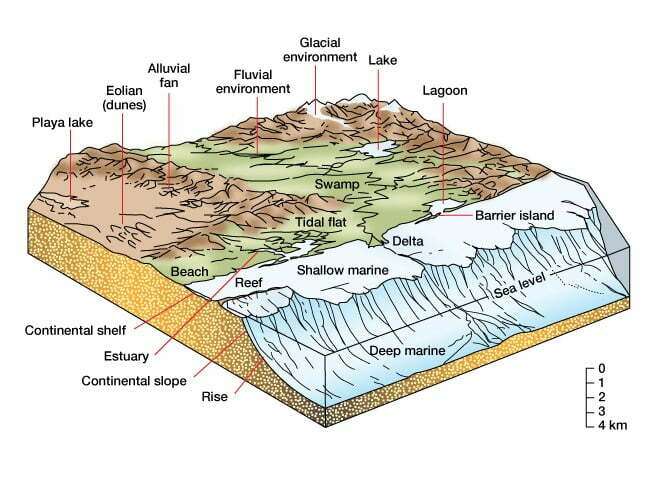

Understanding the lithology of the rock cored is important because changes in the lithology indicate variations in the chemical and physical properties, as well as in the sediment’s depositional environment (Figure 1). Changes in lithology give rise to changes in grain density, natural radioactivity, acoustic properties and resistivity, all of which are important in formation evaluation and, in particular, in understanding the downhole wireline and/or LWD well log responses.

The lithological description of cores should follow a basic format similar to that used in the description of ditch cuttings. The American Association of Petroleum Geologists, among many others, have published detailed instructions on sample description methodology. If more than one lithology or interbedded lithologies occur within an interval, the percentage volume of each lithology should be estimated. The contacts between lithologies should be identified as gradational, interbedded or sharp, some of which will be erosional and may represent unconformity surfaces.

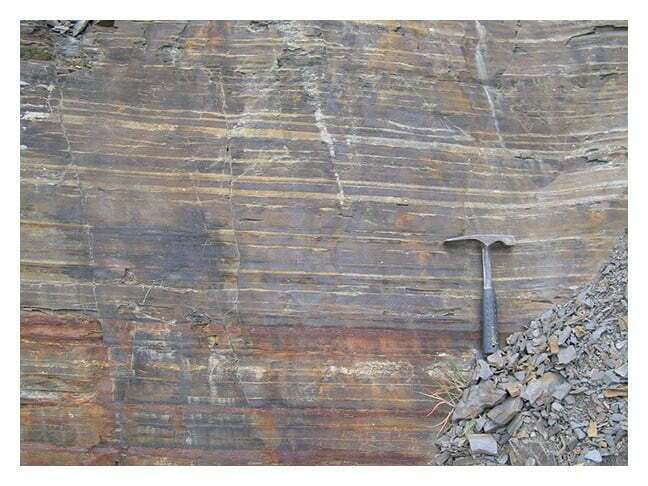

Hydrocarbon reservoir rock types in conventional reservoirs usually break down into sandstones (clastic rocks), composed predominantly of siliceous grains (SiO2), carbonates, composed of limestone (CaCO3) and dolomite (CaMgCO3) or, in unconventional reservoirs, shales and coals. Coarse-grained sandstones tend to make high quality reservoirs, but with reducing grain size, eventually degrade into siltstones (Figure 2) which may also be of commercial reservoir quality but often with significantly reduced permeability.

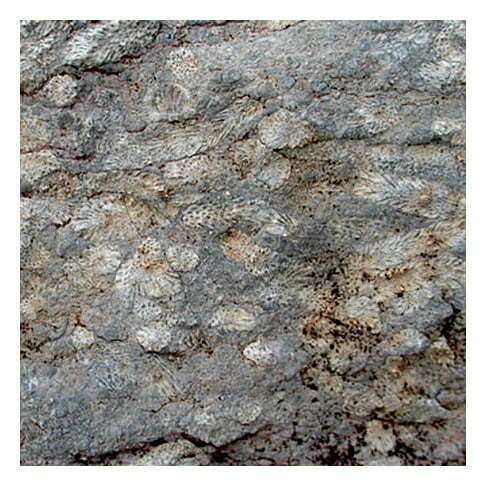

Carbonates (Figure 3) are sedimentary rocks formed at, or near, the earth’s surface by precipitation from solution at surface temperatures, or by the accumulation and lithification of fragments of pre-existing rocks or the remains of organisms.

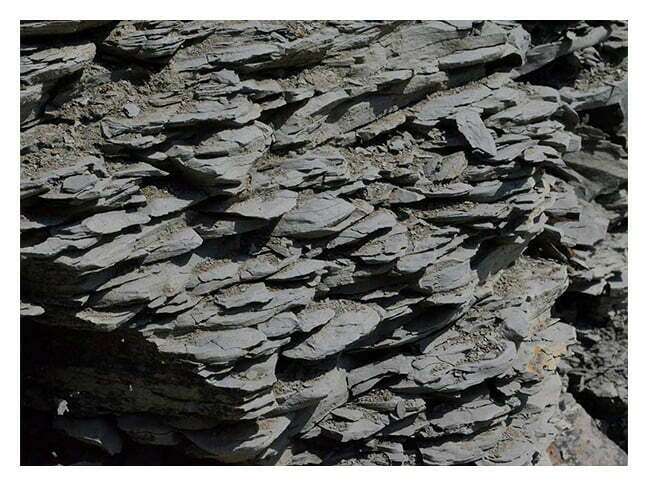

Shales (Figure 4) will also be encountered in cores, either as reservoirs in unconventional shale oil and gas plays or as non-reservoir intervals and seals in conventional hydrocarbon accumulations. Shale gas is natural gas stored in rocks that are rich in organic material, such as dark-colored shale. Gas shales are often both the source rocks and the reservoir for the natural gas, which is stored in three ways:

- Adsorbed onto insoluble organic matter, kerogen, that forms a molecular or atomic film

- Trapped in the pore spaces of the fine-grained sediments interbedded with shale, much like in conventional reservoirs

- Confined in fractures within the shale itself

Organic-rich shales, which traditionally have been viewed as source rocks and cap rocks for conventional hydrocarbon accumulations, are also now viewed as unconventional reservoir rocks in certain situations. Unlike a conventional oil and gas reservoir, in which the trapping mechanism limits the extent of a hydrocarbon accumulation, shale oil and gas reservoirs can be a continuous layer of hydrocarbon-bearing rock, often pervasive over a large area.

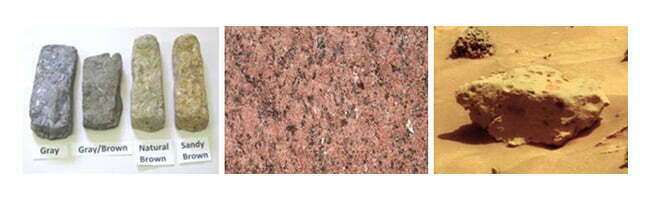

The color of the core varies from all shades of gray through brown, and brown through reds and yellows (Figure 5). The color may be uniform or it may be mottled, spotted or banded. In those areas where the most productive rocks exhibit essentially the same color, this property may occasionally be omitted from core analysis reports.

Thickness of Units

A physical examination and thorough description of the core allows the thicknesses of geological units to be described down to at least the centimeter scale and even to the millimeter scale, if required. Many authors suggest that the smallest feature which is realistic to show in core descriptions should be 0.05 inches in height. Such vertical resolution is significantly superior to even the most sophisticated, modern well logging tools which average their readings over the logged interval according to the vertical resolution of the specific wireline or LWD tool in question.

Petro Shine The Place for Oil and Gas Professionals.

Petro Shine The Place for Oil and Gas Professionals.