Core Photography

Core photography options range from black and white photographs, to color photography under natural light, to pictures taken under ultra-violet light (Figure 1). Photographs are often taken of the core before it is slabbed, with any residual hydrocarbons still in place. The color and ultra-violet light photographs tend to complement one another, the color recording what the eye sees and the ultra-violet revealing oil fluorescence and, hence, the location of hydrocarbons.

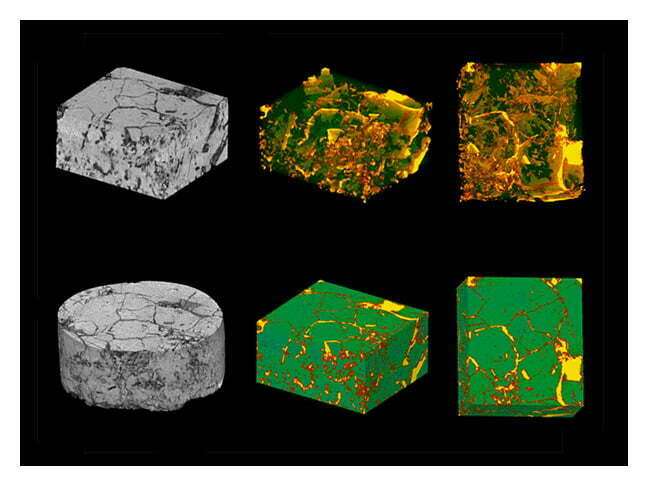

In reservoirs that are fractured (Figure 2), enhancement of the fracture pattern is sometimes observed using the ultra-violet light photographs.

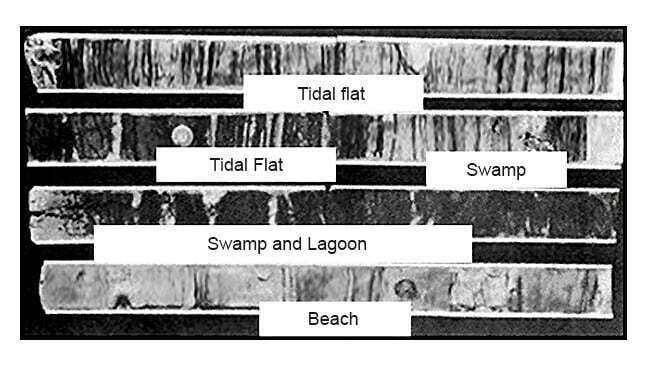

Photographs are often taken at 1 ft (30 cm) intervals along the core. In other cases, the cores are grouped into lengths of 15 or 20 ft (4.5 or 6.1 m), and a single photograph is made of the entire sequence. Some detail of the core may be lost in the multiple footage shots, but changes in facies and lithology as well as core structures are sometimes observed better this way. While laminations and other core structures are often visible on non-slabbed core, they are normally easier to study on a core that has been cleaned and slabbed before being photographed (Vinci, 2014).

Multiple footage photos, such as those shown in Figure 3, are helpful for seeing changes in the core bedding and structures that indicate differences in permeability, porosity and the depositional environment. Thomas (2011) describes a process for deriving lithology from core photographs.

Photographs form a permanent record of the core’s appearance and can be easily sent to coventurers and other interested parties. A photographic record is invaluable in reservoir studies when the physical rock is no longer available. Written lithological descriptions are important, but they are well complemented by the photographic record, revealing zonal transitions, stained sections, minerals, fractures, dips, stylolites, shale partings and other critical formation indicators. Geological interpretations may change as additional wells are drilled and new data becomes available. In such cases, a permanent record of the core’s appearance is a very helpful tool.

Petro Shine The Place for Oil and Gas Professionals.

Petro Shine The Place for Oil and Gas Professionals.