Directional Permeability

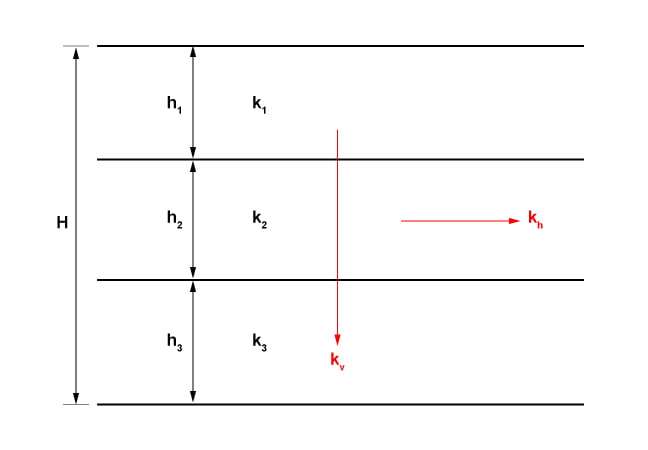

The permeability of rocks normally varies in different directions (Figure 1 ) because rocks generally have some anisotropy.

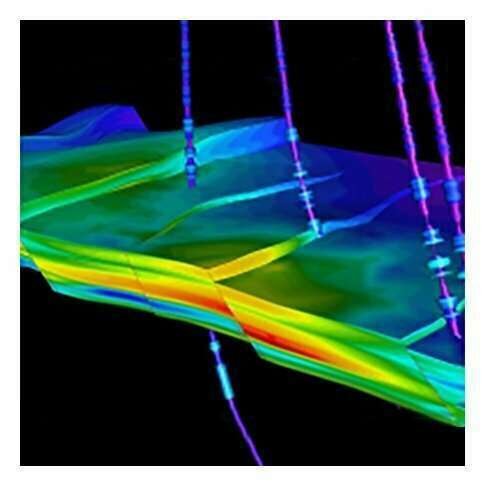

Figure 2 illustrates a reservoir model with horizontal permeability channels.

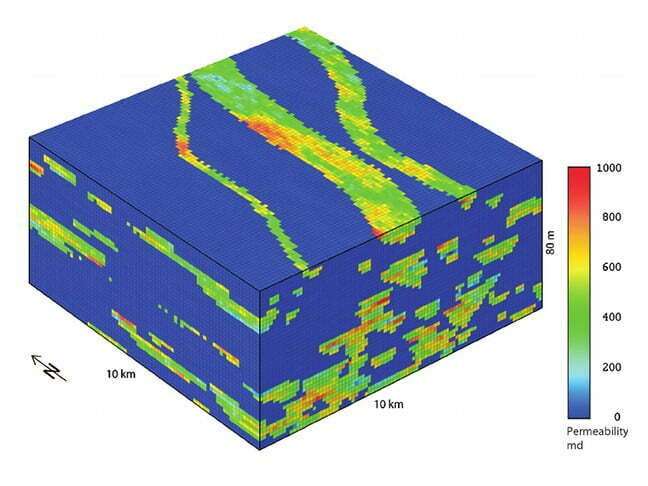

For effective dynamic reservoir modeling, differences in the horizontal and vertical permeabilities of reservoirs must be well understood. Figure 3 shows a geostatistical permeability realization used for numerical simulation.

In both sandstone and carbonate reservoirs, it is common to find low permeability zones that may sometimes be only millimeters thick yet serve as effective barriers to vertical flow (Mavor, 2014). In such a case, the vertical permeability of a formation is only a small fraction of the horizontal permeability.

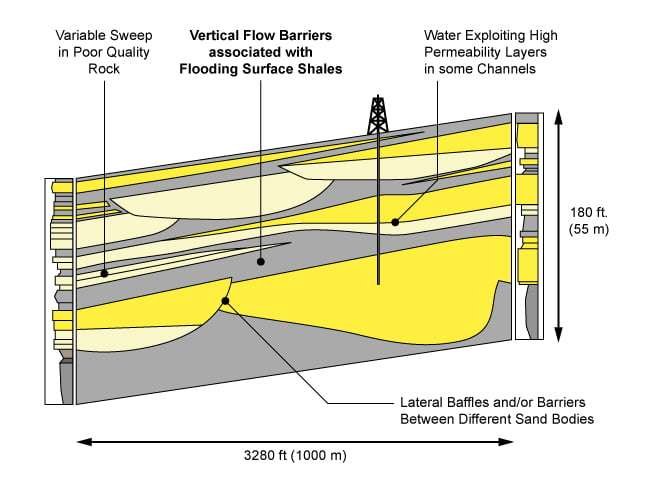

A lack of data on horizontal and vertical permeabilities can result in inappropriate completion practices, or the installation of an enhanced recovery scheme that does not work well, or both. In one example, a crestal injection of liquefied petroleum gas was used to improve the displacement efficiency from pinnacle reef reservoirs. However, in some instances, vertical flow barriers extending over large horizontal distances (Figure 4) caused a holdup of the downward advancing liquefied hydrocarbon fluids and unanticipated high residual oil saturation in the non-contacted zones.

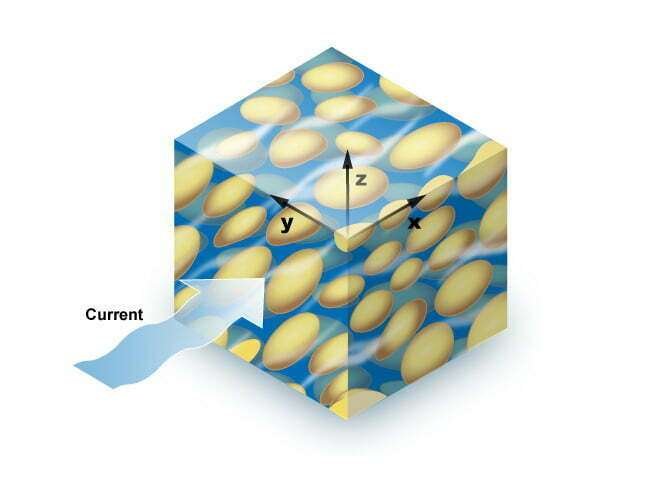

In formations where differences in the vertical and horizontal permeability may not be significant, there may still be a preferred permeability direction in the horizontal plane. Many rocks are made up of grains that were transported by, and deposited in, water currents (Figure 5). If the grains were not spherical, they acted like weather vanes they came to rest with their long axis parallel to the current and their largest cross-sectional areas parallel to the earth’s surface. Such preferred grain orientation gives rise to directional permeability.

Laboratory analyses to establish the directional permeability can be made on core plugs cut in different orientations around the core periphery or by conducting directional permeability analysis of full diameter cores. In either case, these data are very informative, especially when they are obtained for oriented cores and reported at 30º to 45° increments around the circumference of the rock. Directional permeability tests are a natural adjunct to oriented core analysis. They can be complemented by studying thin sections cut in specific orientations to explore and explain directional permeability differences.

Petro Shine The Place for Oil and Gas Professionals.

Petro Shine The Place for Oil and Gas Professionals.